|

Francis Conrad Shenstone Frost was the son of Francis and Agnes Frost of Thorrington Hall, Colchester. He had two sisters Dorothy and Ethel. The family had a farming background in both Brent Eleigh, Suffolk and more recently based at Thorrington Hall where they employed a sizeable staff.

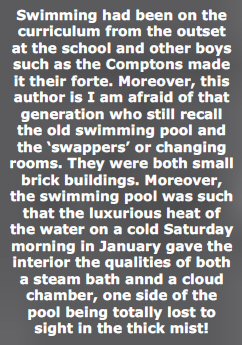

Francis attended Bancrofts in the latter years of the nineteenth century and among his contemporaries were the likes of Percy Lampard and Ernest Meredith. Indeed both these lads were confirmed with Francis by the Bishop of Colchester in the school’s chapel in 1899.

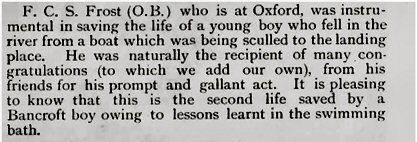

Francis’ father Francis died in 1910 whereon the family moved into a house at 31 Wellesley Road, Colchester. On leaving school Francis obtained a post as a bank clerk with the London and County Banking Company. This for a while saw him working at Romford then moving to take up a post in Oxford which he greatly enjoyed. It was while here in Oxford that we have an insight into an early incident of some heroics when he rescued a child from drowning:

Public service and the abilities of the school to equip their pupils with all that was needed for their future life were strong and admirable themes always. Francis continued to work for the bank. Then on 19th April 1911 Francis married Helen Glenys Radnor at St Leonards, Streatham, South London. It appears the couple moved back to the Colchester area, Francis having achieved a bank posting back in Colchester. Here the couple lived at 25 Shrub End Road.

Certainly, it was from here that he enlisted in the East Kent Regiment ‘The Buffs’ towards the end of 1916. Francis served until in March 1918 as an officer of ‘A’ Company the 7th East Kent Regiment and was posted in the vicinity of St Quentin. The German offensive launched on 21 March 1918 preceded on the heels of the largest bombardment ever seen on the Western Front. The artillery and the intrusion of ‘stormtrooper’ units made everywhere perilous. Dense mist had covered the ground around St Quentin that morning and conditions were such that one soldier scarce knew the fate of the man he was stood or crouched next to.

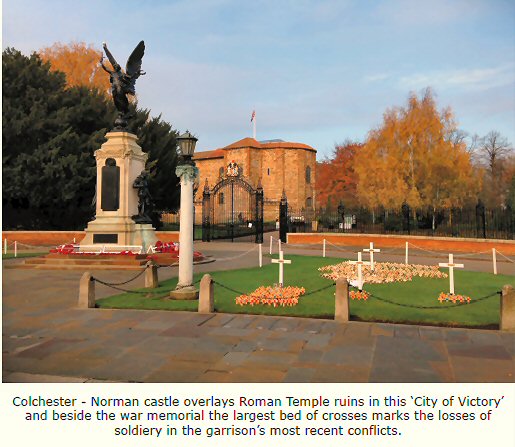

Intrusions of German troops cut off isolated pockets of infantrymen and as night fell there was a scurrying of activity as British units tried in vain to form a coherent defensive line. Such were the conditions that gave rise to the confusion that surrounded the loss of so many. Francis like so many was lost there. It is difficult now to appreciate the scale of losses sustained in the Great War. It is difficult to grasp. It seems a visit to even the most modest of villages witnesses the names of the dead on the war memorial. For Francis the commemoration would be at Colchester. Colchester was a garrison town in 1914 as it is now. Indeed it is one which harks back two millennia to the garrison of the Legions – The City of Victory as the Romans dubbed it.

Here the names of the fallen of the Great War exceed a thousand and remembrance continues to be part of the daily life of a community that has seen more than its fair share of the deaths of soldiers in recent wars. What happened to so many of those hundreds remains unknown. In the Town Hall their names greet every visitor. Francis’ officer’s file shows the absence of information and with it several letters charged with emotion to the authorities and others for months afterwards from his widow seeking any fragment of news of him.

Everyone’s hope in such circumstances was the hope that their loved one had been captured, injured or not, by the German army and that in weeks to come news would arrive that they had survived. Helen Frost and her family interviewed returning soldiers and made appeal too through the Bancroftian for any news.

For weeks perhaps months there were fragments of hope as suggested sightings were reported from prisoners returning from captivity. But the news of Francis’ survival never came. His body was never found. There is a sense that his family never fully recovered from his loss. Thousands besides the fallen were wounded in the Great War.

Perhaps it is this uncertainty felt so keenly by his wife that led to his name never being added to the oak panels which honour our OBs memory. There was certainly correspondence between Helen and the school. Francis’ death left a wife and a daughter. In November 1953 that mother and daughter took their own lives.

Francis’ death is commemorated as are so many on the POZIERES MEMORIAL in the Somme and at Colchester where stand the symbols of peace and war.

|